The recent work of Peter Mohall takes the starting point from two paintings he made in 2007, “Studio View no.1 and no.2”. When allocated a temporary, unpainted studio at the Academy, there were bare walls built with composite wood plates – Oriented Strand Board.

Mohall was fascinated by the turmoil in the structure of these walls. Close-up photographs of the small details were transferred and enlarged on the canvas, with a Gerhard Richter-blurred photorealism. The image was limited to shades of green, to give the impression of a forest landscape. The intention was to create a virtual loop in a visual manner, taking the painting back to the source of its motif – the forest.

.

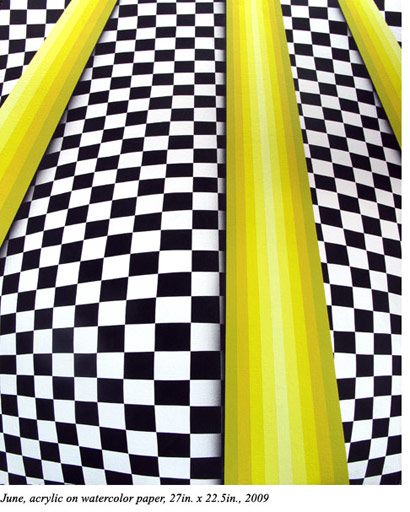

Mohall further extended this project to another series of paintings with the title “Faux Bois”, a reference to the traditional craft of imitating wood-grain. Instead of the norm of imitation of expensive hard woods, he utilised one of the cheapest kind – OSB. The motif is similar to the previous series, though the approach is changed to a more broad use of different painting applications and multiple colours.

In “Faux Bois” the image-composition is investigated through chaos theory. An intuitive system of colour-fields is arranged throughout the canvas to shape the landscape that appears from the almost absolute chaos of the structure within the OSB. A similar phenomenon to cloud spotting, where imaginary figures appear in the sky to the viewer.

“Studio View” and “Faux Bois” are pure studio-based works, where the act of painting is performed, and the motif is excavated within the studio. This working manner resembles the approach of Piet Mondrian with his wall-works, where he also merged the studio into the process of painting, making the project an enclosed environment.

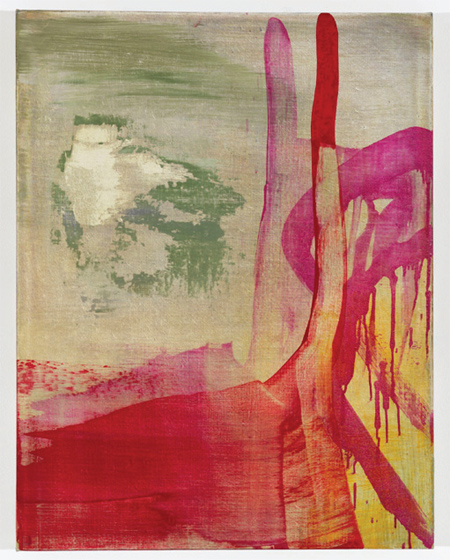

The last year, Mohall has done the opposite and ventured outside in the sourcing of motifs. He has been working with a new project called “Fractal Figuration”. The paintings maintain the fractal imagery that characterizes his former work and place it in a new context. He uses the aesthetics familiar to Jacques Mahé de la Villeglé of the Nouveau Réalisme, using photographs of decayed posters as model, a sort of ready-made décollage

Though all three series are painted after photographic drafts, “Studioview” and “Faux Bois” are perceived as non-objective paintings, this time he turns towards the margins of the figurative. “I’m interested in the deconstruction of the motif’s ability to relate to abstract imagery. While ”Fractal Figuration” obviously is representative, it still has elements resembling abstract works of, for example, Kandinsky and Schwitters.”

The work of Peter Mohall is based on deconstructed motifs. With loose collections of related fragments, the paintings have the characteristics of the architecture conceptualized by Jacques Derrida, Deconstructivism,