The first work of Marius Engh I ever saw had me pretty much seeing nothing. Entering the installation of his graduation exhibition almost ten years ago I was offered nothing more than a pitch dark space. Hesitantly inching my way forward, I realized soon after having turned several corners that the space had also had turned into a labyrinth. I was confronted with a profound doubt regarding the point and purpose of the piece, but more importantly I was doubting my ability to return to the entrance. The solution was somewhere in between: I stood still and hoped for my eyes to adjust to the darkness. Marius Engh’s works have since always required and rewarded in the same manners: wait and there is a chance you’ll be able to see.

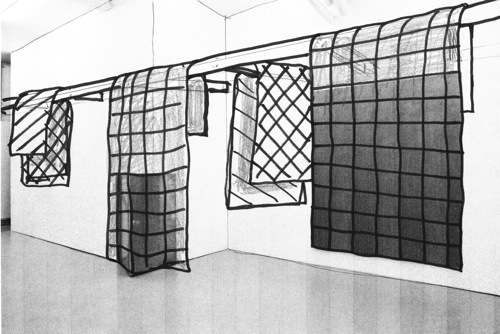

“Time has turned into space, and there will be no more time till I get out of here” – Engh’s choice of title does not only serve as a reminder of the disorientation experienced upon initially encountering his works, but also serves as a reminder of the inherent theatrical qualities to his sculptures and installations. For his third solo exhibition at STANDARD (OSLO) Engh leaves the gallery with a single work; a beam structure running the entire length of the exhibition space from which four quilts in have been suspended. A clear, clean, but yet eerie and empty arrangement. Engh’s work has the incompleteness of a prop or a backdrop, still awaiting its activation by the presence of somebody or something else. Taking its title from Samuel Beckett’s Texts for Nothing (1-13) (1950-52), the installation reveals an interest in a similar form of standstill. Or at least – knowing that a complete condensation of verbal and pictorial information is not permissible – a slowing down of coming into knowing. As is the case with so much of Engh’s work it possesses an annoying quality: an insistence on seemingly insignificant signs that in the absence of alternatives not only have to be trusted as the sole source of information but also trusted to be of some importance.

The pessimism of Michael Fried every so often proves itself purposeful; still waiting for that convenient glimpse of light to interrupt the solid opacity of Engh’s installation, I was reminded that indeed my fumbling around could be what there was. Fried’s seminal essay “Art and Objecthood” (1967) launched an attack on the then contemporary practice of minimalist art and what Fried saw as a location of content in the viewing situation rather than with the work itself – making the viewer’s response (the search for the pictorial content that has been omitted) the matter of concern. Why then even turn on the light? Touché, Monsieur Fried, but then again the question remains (with the fear of sounding zen kitsch): what constitutes absence and what constitutes presence? Rephrasing the question: how have the threshold values of information or notions of iconography (or its absence) been subject to continuous negotiation since Malevich’s monochrome and the void turned pictorial, Yves Klein’s leap into the void, Robert Smithson’s “Museum of the Void” or John Cage’s “4’33″” and the claim that “there is no silence that is not pregnant with sound”?

What Engh offers may, however, not so much be silence as a devaluation or re-evaluation of sign value. The four quilts here on display seem as much motivated by decorative as by communicative ambitions, leaving it unclear whether they are to be stood as mere ornaments or having any significance as signs. Hanging from the naked wooden structure, the four quilts resemble the flags of an optical telegraph where the bold patterns and rich array of colours would serve as syllables. However, the intense sensation of a language unfolding does not prevent the simultaneous sensation of meaning folding in. Recognizing being underprivileged yet again, I merely wait for the muteness to perforate.